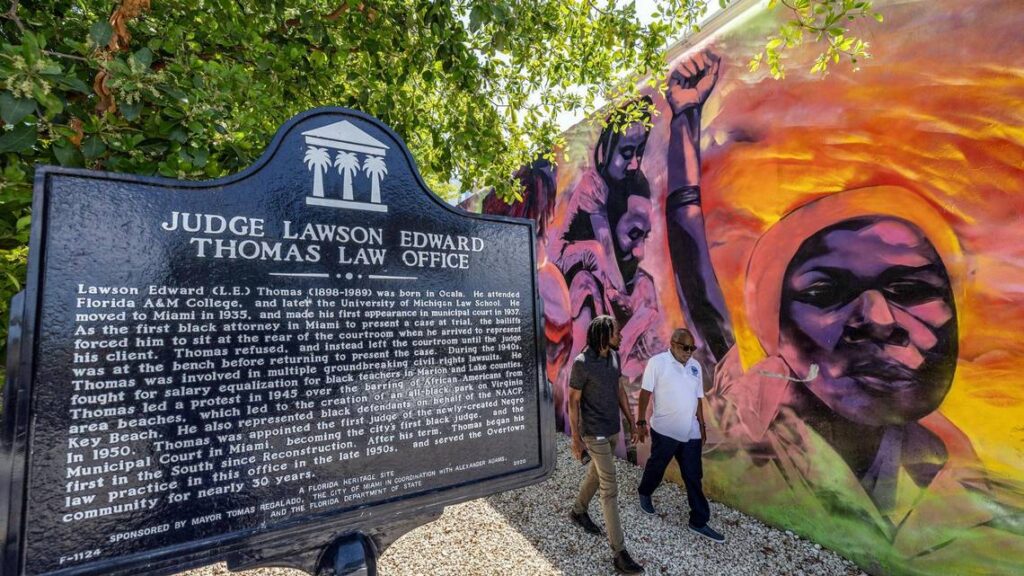

John Charles Thomas recalls fondly what it was like being in his father’s office as a child in the 1960s. The office, which sits along Northwest Second Avenue in Overtown, was where lawyer Lawson E. Thomas worked on high-profile cases, such as fighting for equal education for Black students in Broward County and playing a role in Virginia Key Beach becoming Miami’s first Black beach. “He was highly intelligent but extremely sensitive to the racism that was going on at the time,” the younger Thomas, now 65, said of his dad and his work. Now, Miami’s Southeast Overtown/Park West Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) has taken on the task of preserving the law office, which had fallen into disrepair in the last decade. The historic office will soon be home to an art gallery highlighting Overtown’s rich history after undergoing a $375,000 renovation in the past year.

Efforts to renovate the law office had been a few years in the making. The building, built in 1936, had moisture damage, and the entire front facade needed to be redone. In 2020, the city of Miami listed the office as a historical site, and two years later, the Overtown CRA approached the city about preserving the nearly 90-year-old structure. “Because he was a pioneer in this community, and because one of our many missions is to try to protect historical buildings that are located throughout the community, we felt that that building ranked up there with the historical buildings,” said Overtown CRA President James McQueen.

Renovations to the building were completed toward the end of 2024, and the new art gallery is anticipated to open in April or May.

An exhibit called Sepia Vernacular will display photographs that showcase Overtown’s streetscape from the 1920s to 1950s. Curated by the city of Miami’s planning department, the exhibit was recently on display at the Miami Riverside Center and includes 80 photographs that captured the daily life of Overtown residents during the early part of the 20th century. Those photos were taken for tax purposes, at a time when residents needed to submit a photo of their property before doing any renovations.

“All of those records are in the city’s archive, and those archives paint the story of how Overtown used to look,” said Natalya Sangster, the CRA’s director of operations.

“We wanted to bring it closer to the community so that the residents who actually grew up here can have access to these historical photos and all this information,” she continued. Beyond the art gallery, McQueen hopes the space can be utilized for other purposes longterm. “We envision that sometime in the future, we’ll expand it,” he said.

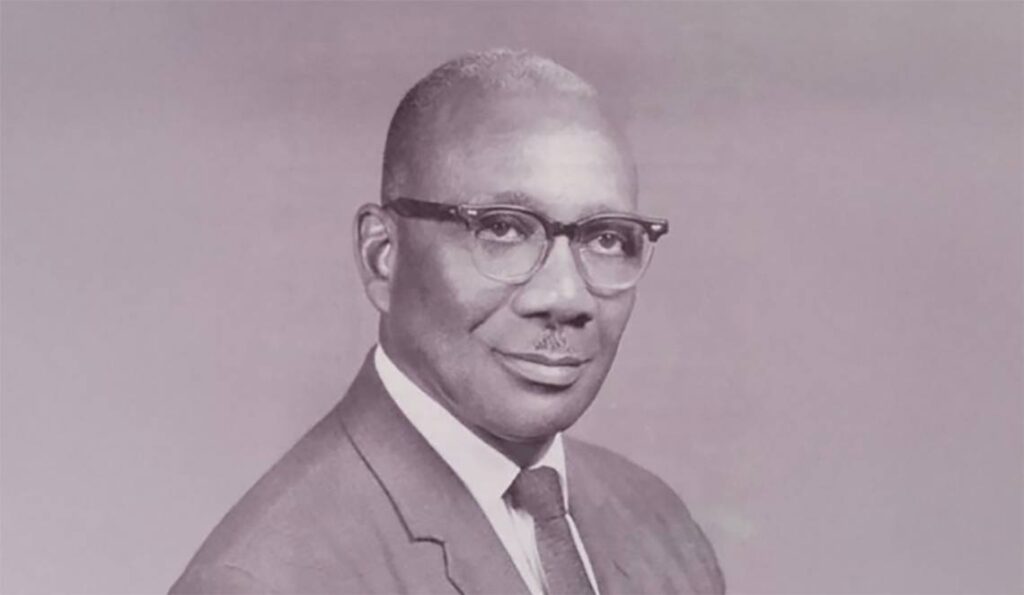

Born in Ocala, Thomas attended Florida A&M University when it was called Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes and moved back to Ocala to teach for a few years before going to the University of Michigan’s law school, his son recalled. Thomas worked in Jacksonville for two years before moving to Miami in 1935. He purchased the office shortly after his arrival, working with a law partner briefly before ultimately flying solo.

The younger Thomas recounted the story of his father becoming the first Black lawyer to represent a client in court. Lawson Thomas had attempted to go in front of a railing to be near his client when a bailiff told him he couldn’t do so. “He said, ‘Get back, N-word, or I’ll throw you out the fourth-floor window,’” he recalled his dad telling him. When his client was called, Thomas told the judge what had happened, to which the judge said he could practice in front of the railing. “That was sort of his first introduction, he told me, to the Dade County court system.”

Thomas took on murder and civil rights cases, often arguing for the rights of Black residents in Miami. His most prominent work involved the 1940s wade-ins, in which he and other prominent Black attorneys planned protests to desegregate beaches in South Florida, eventually leading to Dade County officials offering Virginia Key Beach as Miami’s first Black beach. In 1950, Thomas was appointed judge of the neighborhood’s Black municipal court, a segregated court, making him the first Black judge in the South since Reconstruction. “I knew that there was something special about him because of the way people would react to him,” John Thomas said of his father.

In 2000, about a decade after Thomas’ death, the downtown Miami courthouse was named in his honor. McQueen said preserving Thomas’ legacy is crucial at a time when Black history is being limited in how it is taught. “We’re challenged now, and the whole mood in this country, it seems to me, is to erase our history,” he said. “So at the CRA, we feel like it’s our responsibility and obligation to do all that we can to maintain it so that our kids can see where they come from.” John Thomas echoed those sentiments. “Those efforts won’t amount to anything. We as Black people have been brought over here, we have been in the Middle Passage, and way before that, we’ve been enslaved. We’ve had laws against us during the Jim Crow era. We’ve been brutalized, we’ve been shot and killed, and yet we’re still standing,” he said. “Our history will never go away, so there’s nothing you can do to stop us from maintaining and sustaining our history, because we are what America is all about.”

Read more at: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article302700024.html#storylink=cpy